UK Manufacturing Is On The Up And Its Maintenance Teams Are The Unsung Heroes

UK Manufacturing Is On The Up And Its Maintenance Teams Are The Unsung Heroes

Alan Whetstone, Managing Director of ERIKS UK, argues that maintenance teams need to be given a share of the credit for the UK’s manufacturing renaissance. (Read More)

The long term trend of Purchasing Managers Index is now consistently above the 50 point mark which signifies growth – a clear demonstration that the manufacturing sector is in good health.

There are a number of reasons behind this outlook. Whilst short-term factors like the oil price will inevitably have a positive impact, my own view is that the UK is now reaping the benefit of sustained investment over many years, in part fuelled by low interest rates. This has enabled manufacturers to invest in new state-of-the-art plant and machinery which has increased overall efficiency, productivity and competitiveness.

However, whilst the UK’s manufacturing success is cause for celebration, in each factory, process plant and industrial site there are vital contributors to this success who are being, once again, overlooked.

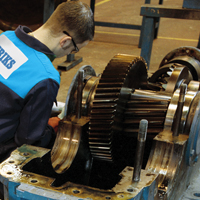

The maintenance teams who keep this equipment working deserve a lot of credit for helping deliver these numbers in often exceptionally difficult circumstances. Because, as industrial technology has taken giant leaps forward over the last decade, our maintenance teams have been stretched ever thinner.

The primary driver of this situation is the complexity of the technology used in modern machinery. A modern servo drive system found in CNC machining, factory automation applications and robotics, to name but a few potential applications, is a much more complex piece of machinery compared to traditional DC or AC motors, particularly in terms of its ability to give motor feedback during operation. In fact, a number of surveys recently have made the point that the outsourcing of maintenance for complex machinery is increasing because of the impracticality of maintenance teams being able to do the job themselves.

What’s more the breadth of equipment that is being maintained has grown dramatically. Nowadays the range of equipment used in production environments ranges from air flow equipment through to electrical test, high voltage and gas detection, through to tooling to torque wrenches, calipers and micrometers.

In turn, the complexity of test and calibration equipment has increased to keep pace with this technology and breadth of equipment. Proper asset management nowadays involves the regular inspection and calibration to ensure safety, accuracy and compliance with the relevant regulations. In effect, maintenance engineers have been hit with a double whammy of an ever growing range of more and more complex equipment.

Whilst there can be little doubt that the maintenance engineer’s job has got more and more challenging, there is little evidence that production departments are creating the ideal conditions for maintenance to succeed.

One of the oldest arguments in industry is between production and maintenance, with those responsible for maintenance, repairs and operations (MRO) wanting access to machines in order to perform essential service and repair work, whilst production is unable to release machines because of the inevitable impact on output.

This is the root of the problem, namely maintenance and production teams, which should be on the same side, being pulled apart by conflicting objectives.

In Japan, the model is very different, with the philosophy being for all machines to have an element of spare capacity to allow time for preventive maintenance. This means that if there is a machine breakdown, the idle machine can be brought online and production continued. What’s more, it ensures that maintenance engineers can prioritise preventive maintenance work over knee-jerk breakdowns.

My worry, is that in the UK, production targets demand that our packaging machines, conveyors, machine tools and lifting equipment are working 24/7 with no time for proper inspection and maintenance. For the UK’s manufacturing statistics to be in such rude health in these circumstances is nothing short of a remarkable achievement, but I do wonder if we can keep going like this indefinitely.

All of which makes you wonder what would be possible if we actually built-in some machine redundancy time and gave maintenance people the opportunity to dig a little deeper and identify whether a bearing is going to fail, or a spindle is nearing the end of its life or if a ball screw needs changing. How much better would our manufacturing statistics be if we gave our maintenance teams the chance to plan, predict and prevent?

The danger is that our ever more impressive manufacturing output statistics lead to complacency. I don’t mean to tar every manufacturer with the same brush, because there are some outstanding examples of maintenance best practice in the UK, but the truth of the matter is that our maintenance practices do lag behind many of our foreign competitors. In order to maintain our competitiveness we need a change of mindset in UK manufacturing that sees maintenance and production teams working in partnership to shared objectives, which in turn will mean that maintenance is regarded as a vital cog in the production process, and a potential profit generator, not just a cost to the business.”

For more information on ERIKS, please visit: www.eriks.co.uk.